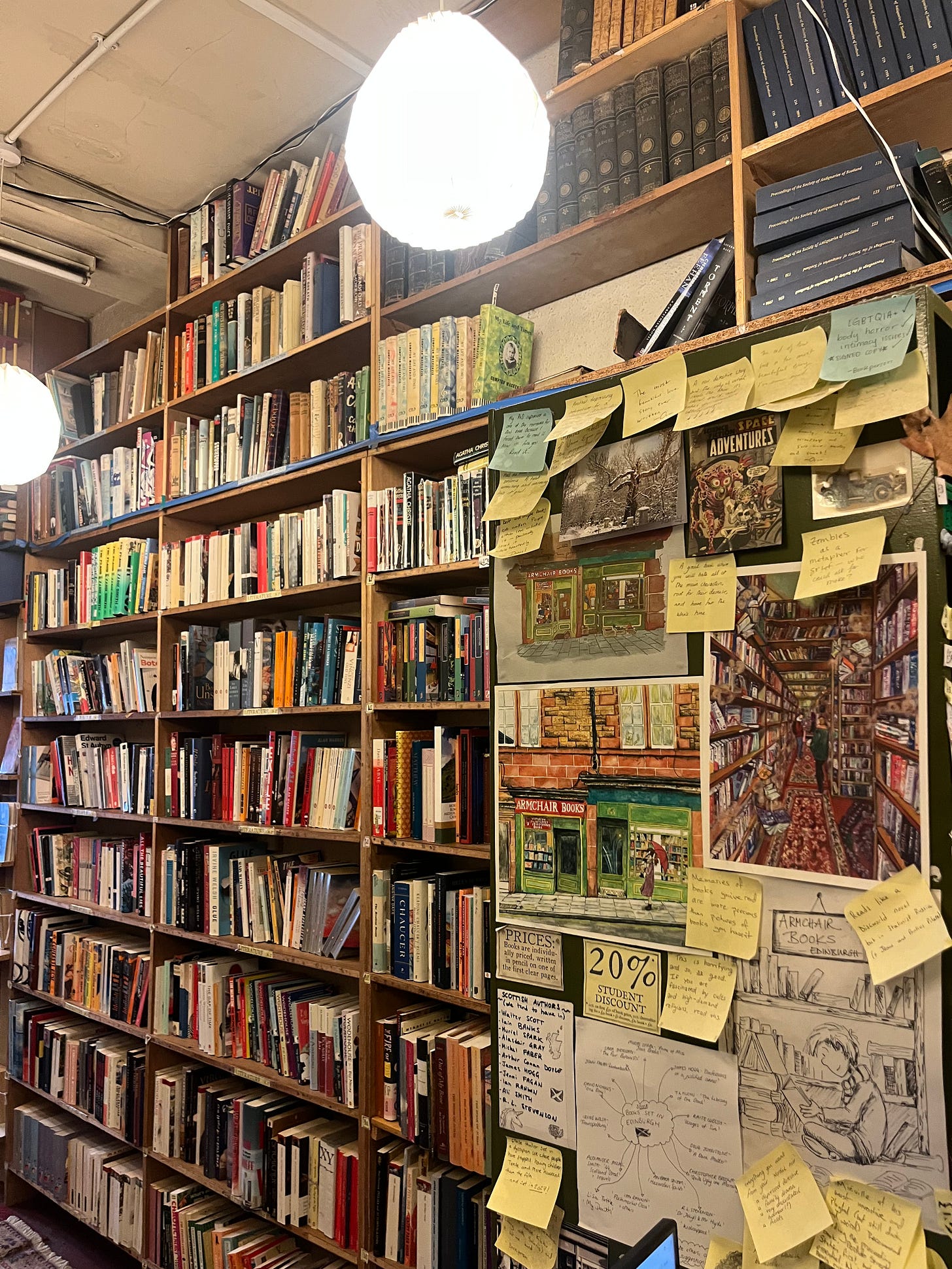

We were in Scotland over the weekend for a wedding which meant that we got to frequent a few of our favourite bookstores. If you ever find yourself in Edinburgh and have room in your suitcase for books let me commend to you two in particular: Armchair Books and Edinburgh books. Both are used and antiquarian book shops in what I have recently learned is the “book quarter” of Edinburgh. I rarely leave without having acquired some treasure. This visit, I bought two books I’d been meaning to read: Normal People by Sally Rooney and The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton. Catton is the youngest writer ever to win the Booker Prize, and Rooney is said to capture the millennial spirit. These purchases were inspired by my desire to read more contemporary novels, especially by working, young, and thoughtful women. I know these are both “old” by publishing calendar standards, but I’ve been wanting to read them and they were a good price!

I’ve been working on my “woman book” (as I’ve been indecorously calling it in my mind) which is a creative project, closer to fiction than I’ve ever gone before. So in addition to the historic research I’ve been doing for it, I wanted to expose myself to some contemporary fiction. See what people are up to, explore new ways of writing, stimulate my creativity. Or something like that. And on that note, since I haven’t done it in a while I thought I’d share with you what I’ve been reading of late, and what I think of it. Much of what I’ve been reading has been inspired by or inspiring my work on my woman book (if you have no idea what I’m talking about, I shared a bit about it here). So without further ado…

Portraits of a Mother by Shusako Endo

As the books and culture editor at Plough, usually I’m assigning other people to review books, but occasionally I just do it myself. And I really enjoyed getting to review Portraits of a Mother. Shusako Endo (1923-1996) is best known in the West for his book Silence which was adapted into a movie by Martin Scorsese. It tells the story of a Portuguese missionary priest to Japan. Japan famously closed itself off to foreigners in the seventeenth century, fearful of attempts at colonisation. It likewise fiercely persecuted the few Japanese converts to Christianity, to the extent that it was believed to be completely stamped out. But in the twentieth century, when things began to open up, it was revealed that some families had never stopped practicing the faith they converted to in the seventeenth century.

Silence is the only book that has ever made me weep in public (I was on an airplane: I covered myself with a scarf and pretended to be asleep). And so I was thrilled when I heard that a brand new novella had been discovered among Endo’s notes. Portraits of a Mother is that new novella alongside a collection of other previous short stories published on similar themes. Although the book is a collection of different stories, it almost reads as one story with recurring characters who shapeshift and recur in different forms and patterns: a troubled child torn between his parents, a passive father who is content with mediocrity and desires to be left alone, a mother with spiritual and intellectual hunger, who practices music until her fingers bleed. These figures, who weave in and out of the stories, were drawn from Endo’s own troubled life. But for all the exploration of brokenness and pain, people disappointing themselves and others, a sense of undeniable, inconvenient grace is poignant. Endo has a way of presenting characters who believe in God despite themselves. I really enjoyed this book.

You can find my review of it in the Editor’s picks of the next issue of Plough.

A way in which I am thankful for this book is it has given me a deeper vision of the idea of a literary “portrait” which is what I hope to do with my “woman” book: offer portraits of these significant figures, windows into who they are.

Book of Margery Kemp by herself

Julian of Norwich was the first woman to write a book in English (that we know of), and Margery Kemp was the first woman to write an autobiography in English. And a fun fact of history (mentioned in Margery’s own autobiography) is that she actually visited Julian of Norwich. One of the chapters in my book has to do with Julian, and so for research purposes, I decided to read the entirety of Margery’s “book,” which I had not done before (I also got a copy of this at a used bookshop, but not in Edinburgh). It is a bit chaotic, but this is the gist of the book: Margery after having quite a few children decides she doesn’t want to have sex with her husband anymore, attempts (but fails!) to have an affair with another man, and then suddenly becomes very pious: which in practice means that she screams and moans every day in church when she thinks about her sins and the death of Jesus, and tells her husband she no longer wants to have sex with him.

In this passage her husband asks her if it were between having sex with him and having his (not her!) head cut off, which would she choose. She says his head being cut off, to which he (understandably) “you are no good wife.”

My take away so far (I’m over halfway in) is that Margery was absolutely bonkers and her husband seems to have been fairly supportive. After this interlude, he eventually makes a deal with Margery that they can have a chaste marriage if she’ll dine with him every Friday (which she initially rejects). He then (unless I’m misunderstanding) supports her in traveling to Jerusalem, along the way of which she visits Julian and alienates a lot of people who get tired of her loud crying. (One does sort of have sympathy for them… it does seem like a lot of crying!). On the whole, it is a very odd book, and less edifying than Julian’s showings.

One thing I find fascinating is that Margery narrates the book in third person, with one exception. When the Bishop agrees to approve of their chaste union, Margery writes: “And the bishop did no more to us on that day, save he made us right good cheer and said we were right welcome.” It seems significant that, despite the struggle and tension between herself and her husband, the only time she speaks of herself in first person is in the “us” of her marriage.

Julian of Norwich: Mystic and Theologian by Grace Jantzen

Another used book shop find: a book by the philosopher and theologian Grace Jantzen about Julian of Norwich. Delightfully, this book included in its pages as a bookmark this postcard from Julian’s cell in Norwich! I’m enjoying this so far, the first two chapters of which are just a nice introduction to what we can (and cannot) know about Julian’s (which was probably not her name!) life. I’m looking forward to getting more into the theological analysis of the text of the Revelations of Divine Love. Reading this (and re-reading the Revelations of Divine Love) has made me notice that by comparison to Julian, Margery doesn’t do much theological reflection her various mystical visions. Whereas Julian’s approach to thinking about her experiences of God’s grace is very methodical, theological, and intellectually rich. I think Julian is often appreciated as a mystic and historic figure, but under appreciated as a theological thinker.

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Because the Luminaries is over eight hundred pages long (!!), I decided to start with Sally Rooney. I’m about one third a way through, and my current feeling is that she is attempting to be George Eliot for Irish teenagers. Lest you think I am reading this into the book, the epigraph quotes Eliot herself:

It is one of the secrets in that change of mental wise which has been fitly named conversion, that to many among us neither heaven nor earth has any revelation till some personality touches theirs with a peculiar influence, subduing them into receptiveness.

George Eliot, Daniel Deronda

It has a veneer of trashy simplicity, but I suspect it is deeper. It reads like a bit chick-lit romance novel: an awkward rich girl beginning a clandestine romance with a popular but poor boy in an Irish secondary school. There is a bit of teenage sexual content (consider this my warning), which one could interpret as mere smut. But I don’t think it is that. In little moments of revelation, she shows how encounter with another person, their quirks and desires and personality and insecurities, can be deeply profound, affecting, and event traumatic. There are hints of Eliot-like-profundity, but I hold out my opinion till I finish. Have any of you read Rooney? Do you have opinions? I’m far behind the trend on Rooney!

Well, friends. I’ve got donuts to eat and a garden to water, so I’ll sign off now. But I’d love to know: what are you reading these days?

Wishing you a lovely Saturday,

Joy

I did Margery alongside Julian when studying Middle English and I am pretty sure I did the obligatory compare-and-contrast essay on the two. I probably did not say in in the essay 'Margery was absolutely bonkers' but wished I could have done, since my main memory is being very exasperated with her and not in the least surprised that so was everyone else. I wonder what Julian thought when Margery turned up at the hatch!

I am currently listening to the audiobook of Pompeii by Robert Harris (who also wrote Conclave) and finding it gripping despite (or perhaps because of) knowing what's going to happen. A water engineer is wondering what might have damaged a stretch of the aqueduct near Pompeii and why does the water smell of sulphur all of a sudden? RUN. RUN AWAY NOW. The question is of course, is the good guy going to get away and is the bad guy going to get a pyroclastic flow up his hypocaust. Here's hoping. While idly looking up facts I discovered the Romans had no word for 'volcano'. You'd think they would invent one after that...

I am dropping my son off this week in Guatemala for hue gap year and in preparation I’ve been reading Men of Maize by Guatemalan Pulitzer winner Miguel Ángel Asturias. It was written in the 40s and is magical realism with flashbacks and between multiple characters. It’s fairly difficult to read but I have enjoyed immersing in the “place” before coming!